Conservatives bemoan the US corporate profit tax rate, which at 35% for the statutory rate is the highest among OECD members. They insist the tax, which they consider to be high, is both unfair and harms US competitiveness. While they acknowledge that the rates the US corporates actually pay are less, due to legal deductions and other mechanisms, what might not be clear is how low US corporate profit taxes have become.

The US Government Accountability Office (GAO, the audit and investigating agency that works for the US Congress) released on July 1 a report on what US corporations in fact pay in corporate profit taxes. Using tax return data (but aggregated to preserve confidentiality), the GAO found that profitable US corporations in 2010 paid federal corporate profit (also called income) taxes at a rate of just 13%, despite the statutory rate of 35%.

If one includes corporations that reported a loss in 2010 (and hence had zero or only little profit taxes due, leaving the numerator the same but whose losses then reduce the denominator in the ratio), the average federal tax rate came to only 17%. Furthermore, the total tax including not just US federal taxes, but also US state and sometimes local taxes as well as profit taxes paid abroad, came to only 17% in 2010 for the corporations reporting profits, and 22% when one includes the loss-makers.

All these rates are far below the statutory federal corporate profit tax rate of 35%, which has been in place since 1993. There are state and sometimes local corporate profit taxes on top of this, with rates that vary from zero in certain states (such as Nevada), up to 12% for the top marginal rate (in Iowa). The state taxes average about 6 1/2%. Taking account of just federal and state taxes, the corporate profit tax rate on average should be over 41%.

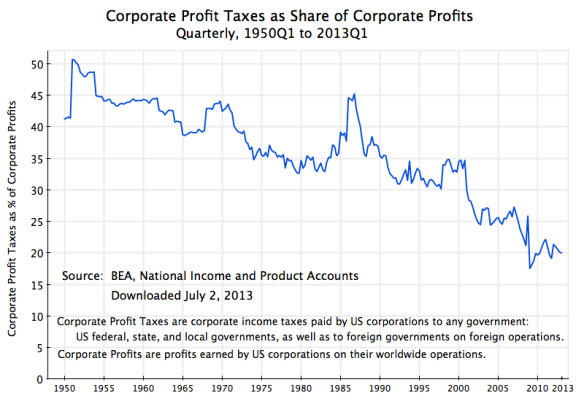

The GAO investigation was carefully done, and has raised again the point that while the US corporate profits tax rate might appear to be high, it bears little relationship to what corporations actually pay. And the trend over time is decidedly downward. The graph above uses data from the National Income and Product (GDP) Accounts, produced by the BEA of the US Department of Commerce to show what corporate profit taxes have been as a share of corporate profits since 1950. While these figures will not be exactly the same as what actual tax return data will show (due to definitional differences in what is included in taxes and especially in how corporate profit is defined, as well as due to timing differences arising from the distinction between when tax obligations are accrued and when they are paid), the trend is clear. Corporate profit taxes as a share of corporate profits have been falling steadily, from over 50% in 1951 to only 20% recently. These estimates from the GDP accounts are consistent with the recent GAO figures based on tax return data, where one should note that the BEA estimates will include loss-making firms as well as profitable ones in their averages.

The fall in the actual rate paid to just 20% in recent years also undermines the argument that a high US corporate profits tax rate has undermined the incentive to produce. Economic performance was better when the profits tax rate paid was much higher than now. The US corporate profits tax rate averaged 44% in the 1950s and 1960s, yet economic growth was strong then. As an earlier post on this blog discussed, economic growth performance in the US was substantially better in the 30 years before 1980 than in the 30 years after.

Furthermore, there is little support in the figures that the US corporate profits tax rate at 35% puts the US at a competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis the other OECD members. While the 35% rate is indeed the highest, the second highest is 34.4% and the third is 33.99% (see the OECD source cited above). Fifteen of the 33 OECD members covered had rates of 25% or above, and a further 10 had rates of 20 to 24.9%. More importantly, all of these OECD members, other than the US, imposed a value-added tax on top of their corporate profits tax (and other taxes). These additional value-added taxes were as high as 27%, and 23 of the 33 OECD members (including essentially all of Europe) had value-added tax rates of 18% or more. Value-added taxes will be taxes on corporate profits (as well as on labor income), and should not be ignored when one is looking at the overall rate of tax on corporate profits.

The ability to avoid taxes on corporate profits has been receiving increasing attention in recent months. Historically, much of this avoidance has been achieved through explicit provisions written into the tax code by Congress for certain subsidies or other government expenditures, which the Congress did not want to explicitly provide for or acknowledge in the budget. Examples include credits for investing in certain locations or for certain purposes (such as R&D), or accelerated depreciation allowances as a mechanism to spur investment. The objectives might well be worthwhile, but by hiding in the tax code what are in reality subsidies, and then keeping them secret due to the privacy of tax return data, such subsidies are likely to be both inefficient and misguided. If subsidies are warranted, it would be better to provide them openly and transparently through the budget.

More recently, large corporations have learned how to use international operations as a means of hiding profits from jurisdictions where they would be subject to tax. Some examples of what US firms have done in the UK to avoid paying taxes there have been recently in the news, and provide good examples of what modern firms can do anywhere, including in the US.

Transfer pricing, while technically illegal, has historically been one mechanism to do this. This appears to have been one of the ways (among others) that Starbucks was able to run highly profitable coffee shops in the UK, but pay nothing in UK profit taxes. Starbucks of the UK would “purchase” coffee beans from a Starbucks subsidiary legally based in Switzerland, which would in turn purchase the coffee beans from around the world. Since commodity trading in Switzerland pays very little tax on the corporate profits generated in such trading, Starbucks could pay the international price for coffee beans through its Swiss subsidiary (even though the beans would never pass physically through Switzerland), and then charge the UK subsidiary a higher price for the beans. This would increase the costs (and hence reduce the profits) of the UK subsidiary, while generating high profits on coffee bean trading in its Swiss subsidiary, where little or no tax was due on such operations. And this could be done in essentially any jurisdiction which does not tax corporate profits.

There were other mechanisms as well that Starbucks appears to have used, including intra-company loans from one subsidiary (based in a low tax jurisdiction) to a subsidiary in a jurisdiction (such as the UK) where corporate profit taxes would be due. This is very similar to transfer pricing on supplies, although here it would be for the supply of capital.

Through these and other mechanisms, Starbucks has been able to avoid, probably legally given the tax code as written, most corporate profit taxes on its UK operations, even though it had consistently reported to analysts on Wall Street that its UK operations were highly profitable. This became such a public relations disaster that in June the company announced that it would voluntarily pay UK profit taxes of £10 million in 2013 and a second £10 million in 2014. Starbucks has shown how corporate profit taxes have become in reality voluntary taxes, paid only to avoid image problems.

Starbucks provides a good example of what modern corporates can do, even though it operates just a simple business of selling coffee. High-tech firms such as Apple are more often in the news since they have generated high profits yet have legally been able to avoid paying taxes on these profits at anything close to the 35% statutory rate. For example, and as reported in a recent Senate investigation, Apple was able to exploit a difference in how corporations are defined in terms of their tax liability in a country, in order to generate profits in an Irish subsidiary which would not be subject to tax in either Ireland or the US.

More generally, US corporates do not have to pay US corporate income tax on profits generated in overseas operations until these profits are brought back to their US companies. This is unlike the case for US citizens, who must pay each year income taxes on income generated everywhere in the world, and not just the US. Because of this provision in the US tax code, Apple and other US corporates have kept accumulated profits legally overseas, so as to avoid paying US profit taxes on them. The total for large US corporates reached an estimated $1.9 trillion as of the end of 2012, with Apple alone accounting for $102 billion. Republicans have pushed for a tax amnesty on the repatriation of such funds, as was done once during the presidency of George W. Bush. But such tax amnesties of course then generate the incentive to hold such profits in untaxed offshore accounts again, in the expectation that an administration in the future will once again grant such an amnesty.

And it has now become straightforward to structure a system of corporate subsidiaries so that almost any company can, if it wishes, make it appear that profits in the US (or indeed any other country, where corporate profit taxes would be due) are close to zero, and instead are high in some low tax or even untaxed jurisdiction such as the Cayman Islands. Transfer pricing is one such mechanism, although technically illegal as prices between corporate subsidiaries are supposed to be “arms-length” market prices. But these are effectively impossible to enforce. How does a tax-audit determine what the price should have been for some specialized input (such as a component going into an iPad), for which no market exists?

But there are other means as well. High tech firms such as Apple can, for example, transfer ownership of some patent to an Apple subsidiary in the Cayman Islands, and then require the Apple US firm to pay a royalty to the Apple Cayman Islands firm. Or Starbucks can transfer ownership to the Starbucks brand name similarly to a subsidiary in some low tax or no tax off-shore jurisdiction, and then have the US subsidiaries pay that off-shore subsidiary for the use of that brand name.

The legal “technology” for corporate tax avoidance has therefore come to the point where what is in fact paid in corporate profit taxes can be close to voluntary. Starbucks in the UK is the most clear case so far. Governments are concerned, as these mechanisms can now undermine, quite legally, collections on what was at one point an important tax. The OECD now has a working group looking at possible reforms to address the currently legal ability of modern corporates to avoid taxes through their international operations, with a report scheduled to be released in July. But it remains to be seen whether politically possible changes in the tax code will be able to ensure such loopholes are closed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.